The day-by-day, story-behind-the-story of covering the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey.

My Harvey

Sept. 5

Ah, so nice. Heat on in the Uber at 5:45 a.m. It's not that cold in Chicago, but it's chilly enough this early to make that a pleasant perk. That and the classical music the driver is playing. So peaceful. Reminds me of the music my dad used to wake to early before work.

Meatingplace Managing Editor Tom Johnston visited Houston after Hurricane Harvey to cover the meat industry’s impact and response.

A comfortable way to begin a trip to Houston, where I'm flying to see the uncomfortable aftermath of what could become the country's most devastating hurricane in recorded history. More than 50 inches of rain made America’s fourth-largest city hell's swamp. My job is to get the stories of impacted meat industry people. I've already sent the addresses of meat plants to contacts there, including my hometown friend, Kelly, who now lives there with her husband — a local firefighter — and two young boys. I’ll be bunking at her house in Conroe, a good 50 miles straight north from Houston.

Kelly knows many of the locations. One of her texts: “Are you familiar with a gun?” She's a funny person, and that makes me laugh. But she's kind of serious, and even adds, "May want to have a gun in the car." Sucks to have to say, to a former Marine and hunting enthusiast, that I've never shot a gun in my life.

Bang goes reality. You don't know what you're getting into, Tom.

But Kelly later allows that it seems most of these places are off main roads, or at least relatively safe, and so she dials it down.

Slowly but not so surely, a plan is coming into place. I'd convinced my company that we had to be down here, that in this catastrophe there'd be stories to tell. Phone calls to meat plants in Houston in the last week have been prone to fetch only busy signals, so concrete contacts are few at this point. My first stop, however, will likely be the Montgomery County Fairgrounds in Conroe, where Tyson Foods is distributing meals to the displaced, including many of their own local workers. I hope to get their stories. Or maybe I first try to check out one or two plant locations that Kelly guesses might still be sitting in water and capture those images.

On the flight down there, next to me is a young man with glasses and a thick, well-kept black beard who says he's going there with Cardinal Health to help relief efforts. I tell him that on the descent I'd like to trade seats so that I might video the scene below. Most of the water's receded, I'm told, but this view should show what's left. Across the aisle is a plain, young woman with straight, shoulder-length brown hair and glasses. She's reading religious materials, and a rosary dangles from her wrist.

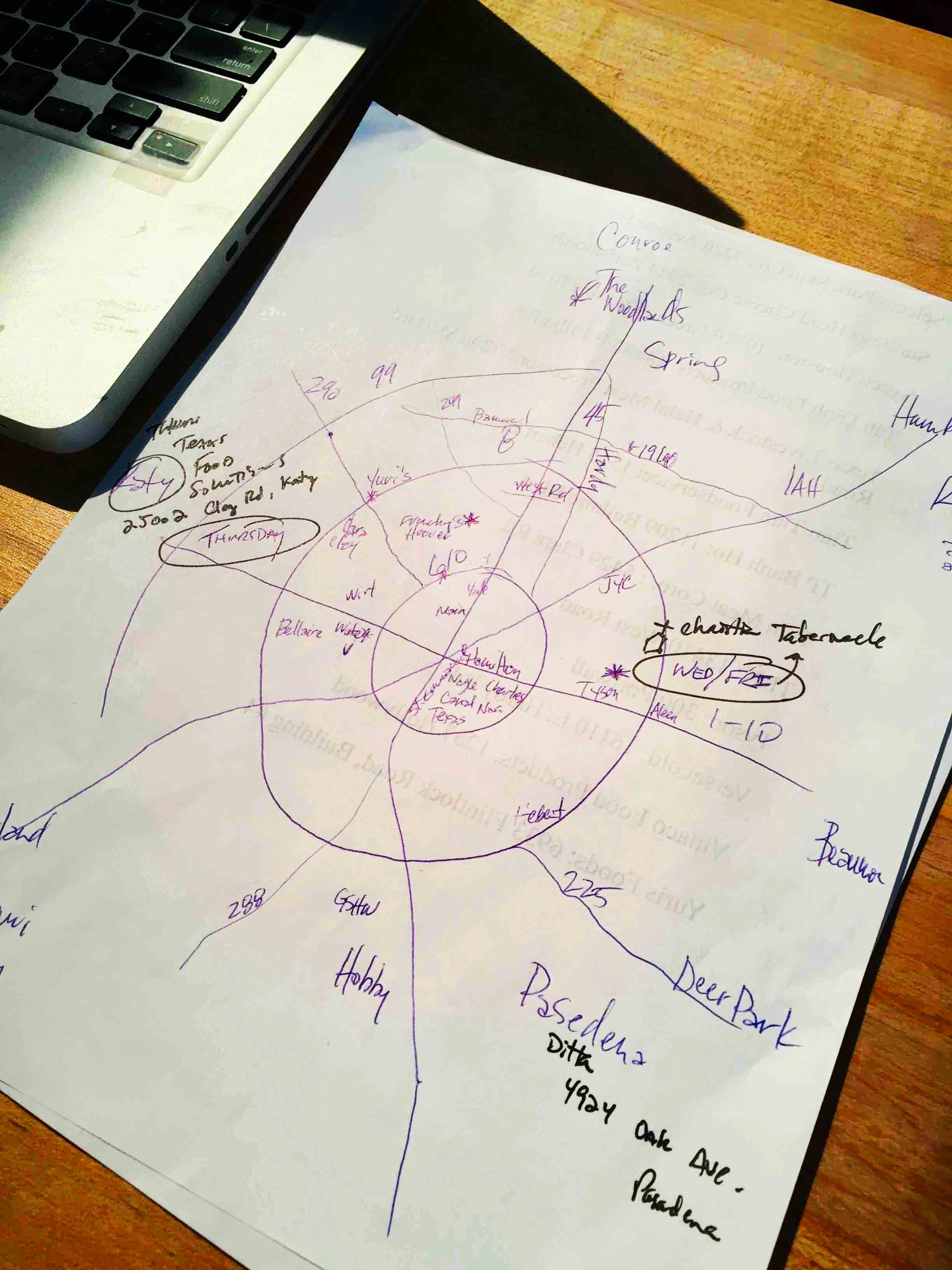

A crude, hand-sketched map of Houston takes the shape of a bull’s-eye Photo credit: Tom Johnston

On descent, I see scant evidence of a catastrophic storm. It is, after all, 11 days afterward. Still, while most floodwater has left, sections west of the city, for example — as I would later see on the news — still have jaw-droppingly deep flooding.

Just outside the airport, I figure I’ll try to check off a couple nearby addresses on my way to the Tyson camp. I make my way to Versacold. Turns out it's Americold now, it doesn't process meat (you liar, FSIS plant list) and, according to the lady who first offered me her help, wasn't affected. Strange (I'd been told it's in the same area where Houston Police Sgt. Steve Perez drowned in floodwaters near the Hardy Toll Road). Ditto at jerky processor Amininchi Foods, although my colleague had been told earlier in the day that they were affected.

I take it that answers, stories aren't always going to come easily. As quite literally is caused by flooding that remains in some areas, there will be dead ends.

My hosts are doing their best to help, tirelessly looking up addresses of local meat suppliers and letting me know what's wet, or used to be. That night, while I've accomplished mostly nothing other than visiting the Tyson camp and getting the lay of the land, Kelly draws a map of greater Houston which, when done, looks like a big bull’s-eye.

Sept. 6

In the morning, I decide I’m going to visit the Tyson outpost again, but first I need a video card reader. I need to transfer a bunch of video footage I took yesterday to make room for more today. On the way there, I stop at a Best Buy, just off I-45. You’d have a hard time not running into whatever big box store you’d want in this big box of urban sprawl.

Anyway, I make my purchase and leave the store. In the parking lot, I open the driver’s side door to my rental and it dings the passenger side door of the car next to me. The snap of a women's neck toward me from the driver seat startles me as much as the ding did her. I look in, mouth a sorry. She uses her arm to wave me away as if to say, “Don't worry about it.” She continues to scroll through her phone. I get in my car, start the engine quickly as to take full advantage of her generosity and leave, quickly. She decides to get out of her Hyundai Accent and walk around to do an audit. Crap, I think. It's just a tiny scratch, but you never know. I get out, too. But again she waves me off. "It's just a car," she says.

River Plantation, north of Houston, was devastated by Hurricane Harvey’s floodwaters. In this YouTube video, residents use wave runners to assess the damage.

She is despondent, but trying hard to be friendly. She made a local reference she figured I’d know, but I told her I was not from the area. Seeing the curious look on her face, I explained that I’m in town to report on the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey.

“Well, if you want to see some visual impact, go over to River Plantation,” she says. That’s the subdivision where she lives. Or lived.

“We lost everything.” She’s staying strong with those words, breathing through them. She expresses her dissatisfaction with FEMA housing. It’s when she remembers the volunteers coming through the neighborhood and passing out food that she starts to choke up.

So, yeah. That tiny scratch on her car? Nothing.

I follow her directions and enter her neighborhood. At first, I think she must have been exaggerating, because I don’t see much. I have to take some turns, round some corners, and finally I come upon a street flanked on both sides with endless piles of garbage that had been ripped out of these large flooded homes. I get out of my car and walk up and down the street, videotaping and shooting photos. As I’m doing that I catch the eye of a resident in her driveway and pause, but she says, “It’s OK, you can take pictures of my garbage.” As I would learn in later days, too, residents here had become used to media presence; the West Fork San Jacinto River runs through here and flooding reached a full story high. That’s to say that if you owned a ranch home, your roof might have remained above water. Aside from that, my new acquaintance is a good-natured, good sport about her situation. Her complaints about the city’s decision to release reservoirs, exacerbating flooding in her area, amount more to sarcasm than overt anger. She’s inclined to sell her house, but what price could she fetch now?

It’s late morning by the time I leave, and I miss the rush of people picking up food at the Tyson camp. But I do some more interviews and check in again with the coordinator, Pat Bourke, who happens to get a call from the pastor at Christian Tabernacle Church. It’s on the east side of Houston, near an eerily named area called Seclusion Estates, and Bourke calls it “ground zero.” This area got hammered, and floodwaters from the Greens Bayou and San Jacinto River lay claim, I’m later told, to about half of Harvey’s fatalities; they include a family of six — two elderly and their four great-grandchildren — that succumbed to the Greens Bayou after a failed attempt to escape in a van. Now that the waters have receded, Bourke’s able to move a team down there “closer to the need,” which is how these relief efforts go by design, almost like a military approach. I want to get down there, too, to see what that need looks like. And I know that Tyson has a plant in that area that had to close for a week after the storm. Bourke lets me know to be at Christian Tabernacle on Friday at 10 a.m.

Flooding in River Plantation is gone about 10 days after Hurricane Harvey, but the damage remains in large piles throughout the neighborhood. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

I check out of Camp Tyson and decide it’s time to drive down to the city and roam around with that map that Kelly scrawled for me — that and Google Maps. Ten minutes into a 50 mile-or-so drive down I-45, I recall my conversations last week with Wayne Butler, CEO of egg roll processor Chung’s Gourmet Foods. I’m gonna be down there, might as well stop in. I call him on the way, and he welcomes a visit so long as I make it by 2 p.m. I press a little harder on the gas pedal.

I think it’s just one side street or so that separates Chung’s complex from the University of Houston campus, which strikes me as some odd zoning. And it's difficult to make out where the office is, but after some wandering I find it. It is pretty modest, not the cozy-waiting-room type of place, but hey, the fish tank is a nice touch. I tell the first face I see who I am and whom I want to see, and soon enough Butler meets me. He’s a big man, with salt-and-pepper, wavy hair, a booming voice and strong handshake. I soon learn he was a lineman for University of Wisconsin’s football team decades ago, and he’s starting to feel that in his knees.

He’s a good sport, too, allows me to do a videotaped interview — which I want in order to know how he managed through the storm — and tour the facility. He introduces me to his plant manager, Ronnie Snowton, who I’d later learn was a champion powerlifter and bodybuilder. Made sense, given the physique stretching his polo shirt. He is soft-spoken and super polite, open to telling his Harvey story and generous with each question. When he does edge on frustration, it’s the thought of his landlord not requiring dog owners to pick up their poop, much of which ended up in his house during the flood, and wanting them out of their place to clean up but with the threat of charging them a month’s rent if they didn’t. Afterward, I meet an older man named Vernon, and learn that his cousin drowned in the storm. He was found in a drainage ditch. I offer my condolences. “He was a good guy” is all that Vernon could say.

Back in my car, the ritual resumes. Where to next? Where to next? I recall watching the TV news last night at Kelly’s, in the middle of her having me read off addresses so that she could map them out, and seeing a section of highway still under some 15 feet of water. The street name I remember seeing over the reporter's shoulder is Boheme Street. So I punch that into Google Maps. It’s way out on the west side, near Beltway 8. I’m on the southeast side. Well, here we go.

It takes a good two hours to get there. The interstates were packed, the sidestreets even more so. I’ve never been in worse traffic. I wasn’t even quite sure where I was going. Just this pulsing dot on my digital map.

I make it pretty close to the dot, but when I’m faced with turning left into another logjam, I opt to go right and see a home whose property had become a rather large pond. Despite my mounting frustration over the traffic, I pull into a nearby parking lot, get on foot and get video. This has absolutely nothing to do with the meat industry, but I’m dead set on actually seeing and gathering evidence.

A piano sits awkwardly among the damaged property in front of a house near Beltway 8 on Houston’s west side. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

I get back in the car and drive farther, and look west down a sidestreet and into the sun, which is reflecting sharply off of floodwater that, even this long after the storm, still has cars halfway submerged. I decide I have to turn around. In order to do that, I have to go into another neighborhood where again I see massive piles of debris on the curbs. A grand piano on one lawn looks almost like a funny prank — you know, the ol’ piano-on-the-lawn prank. Some people do have a sense of humor: I read a sign in one debris-strewn lawn that says, “Yard of the year.”

I stay a while on the flooded street. It’s hard to fathom how this much water is still left, and I meet a young dude named Nine, who is flying a drone with one of his buddies. They tell me the cars were nearly fully under water yesterday. They’re steering a drone directly over top of the smashed out car, and, surprisingly to me, Nine says, “I want to see if anyone’s in there.” I can see on the screen the spider-web of a windshield, and my heart starts beating, hoping like hell I do not see a dead body in the car. No one is in there, but based on the condition of the car, they had put up a heck of a fight. The car is as if it were frozen in time, with the water so calm now. It's almost peaceful, apart from the locusts' deafening buzz in the heat.

Drone footage taken Sept. 6, about 11 days after Hurricane Harvey first hit Houston, still shows extensive flooding and damage on and near Beltway 8 on the city’s west side. Credit: Koncept Kit

I mention what I saw on the news the night before and Nine, who lives in the area, suddenly has on his screen a live drone view of Beltway 8, which indeed still looks like a canal. I can’t contain my amazement, and he proceeds to show me a bunch of other footage he’s gathered, including a breathtaking run over what was the Allen Parkway-turned-chocolate milk river heading into the skyline. He agrees to send me footage, and I decide to start the trek back to Conroe — not by way of Beltway 8, of course.

And then a thought comes to my mind:

Cars are still trapped in floodwaters on Sept. 6, about 11 days after Hurricane Harvey first hit Houston, in a neighborhood near Beltway 8 on the city’s west side. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

We are perverse. We want more. More stories. More damage. I find myself driving all over this exhaustingly huge metro area looking for visual impacts of the storm. It's a weird success to achieve, once I do. Like, ‘Oh thank God, I've found cars half submerged in water. I can prove I'm here, that this happened.’ It’s not all that redeeming.

It’s 7 o’clock by now, the sun setting and I’ve missed dinner at Kelly’s house. The thought crosses my mind that I’ve disappointed her 4-year-old son, whose enthusiasm for guests having “sleepovers” has made me a big star in his eyes. His 2-year-old brother could take me or leave me. I guess I did get some points for bringing them Chicago Bears hats, though. As a father of two young kids, too, I find it nice to come back after this long day to happy kids and animated movies they can’t sit still long enough to watch.

On Sept. 7, nearly two weeks after Hurricane Harvey first hit Houston, Buffalo Bayou still swells high enough to reach the footbridge at the Police Officer Memorial in the city’s downtown area. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

Sept. 7

Last week, I had been in contact with Martin Preferred Foods, too, about how they were faring in the storm. They made it out just fine, but I want to meet with them and get an understanding of what it was like. We set up a morning visit at their plant on Houston’s near northwest side, close enough to see the skyline looming just over its shoulder. They get word that Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue might be visiting their plant while I'm going to be there, too. Jackpot, I think, though I know these bigwigs often change plans on a dime.

Highly accommodating, Tammy Smith, the company’s media liaison, set up interviews with Carlos Nevarez and Sabrina Lewis, two of the 71 or so employees (of 375 total) whose homes/property were impacted by the storm, and with president Jeff Tapick. Accommodating, too, in that they promptly have an extra lavalier mic. I’d misplaced mine, and I'm kicking myself. I need these interviews, and I need them to have good sound.

They tell me Nevarez is shy, so he’s not so certain he wants to do video, and that he’ll have to speak in Spanish but a co-worker can translate. I tell them let’s see how it goes, and if at any point he becomes uncomfortable, I can stop the video.

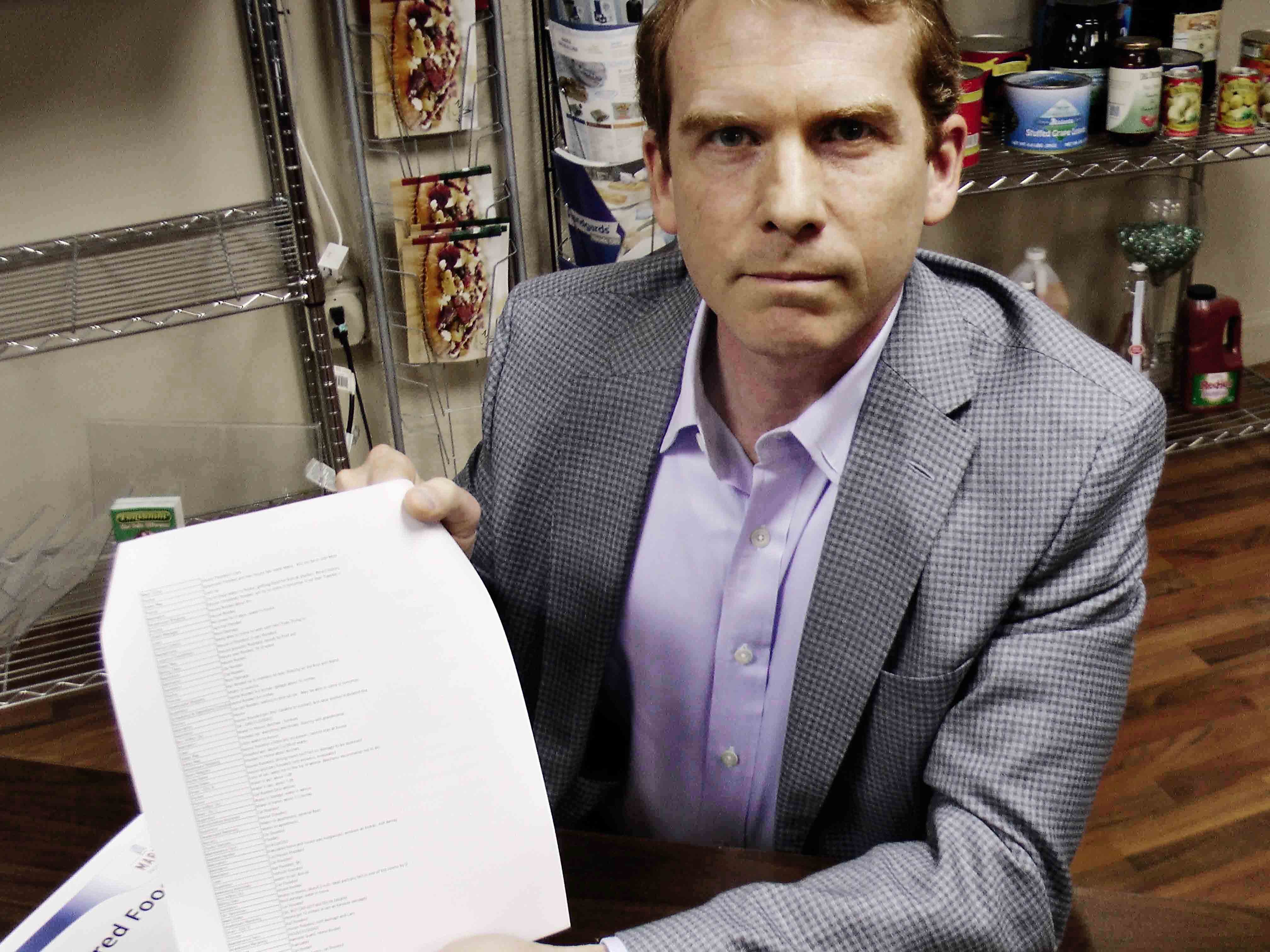

Jeff Tapick, president and CEO of local meat processor Martin Preferred Foods, holds a list of 71 employees and the types of property damage they sustained from Hurricane Harvey. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

We never stop. Nevarez goes on for nearly a half-hour, with almost no interruption from the translator. I can have Andre, a Peruvian co-worker, help me later. I took Spanish throughout high school and college; I actually minored in it, but I was focusing at this point on having the right camera angles and that the microphone was working. I wouldn’t have understood every word anyway — another victim of the use-it-or-lose it theory. But I understand enough to get the trauma he went through. I know the word “llorando,” that he’s speaking of his children crying. I hear that word a few times. I understand also when it gets worse, the roof caving in, and then when he later finds his home has been robbed.

When I’m thanking him for his generosity in telling his story, I ramble and find my voice getting a little shaky. I’m heartbroken for him, but thankfully he, his wife and four children, all under the age of 12, are OK and already are rebuilding.

After finishing that and the other interviews at Martin, and getting some b-roll in the chicken plant, I head out again. Sonny, by the way, canceled and was looking to the next week. He’ll be needed in Florida by then, I thought.

I’m starving, and I haven’t seen what downtown Houston is all about, so I decide to get a bite down there. My server is trying to describe what the scene was down here, where the Buffalo Bayou rose and ravaged. He explains how to get to still-flooded areas along Memorial Parkway. I’m obsessed by now, and head out for more video and photo opportunities. It’s sunny and beautiful and people are out jogging and biking, as they should be. The brown waters of the bayou still bloat enough to nearly wash over the footbridge, normally with far more clearance, at the Police Officer Memorial. As I walk along the banks, a bad move, I have to choose my steps wisely so as to avoid sinking my dress shoes in what had become boggy earth. Hey, I didn’t want Sonny to see me too casual.

After a stop to another nearby processor that is a dead end, business hours are up and so I head back to Conroe. I’m feeling better about the content I’m collecting, but still unsatisfied. It’s so much driving, sometimes for nothing, and sometimes I get hung up on, and sometimes people agree for a visit but then they have to go into a meeting for hours and I need to move on. Tomorrow I go to “ground zero.”

Before then, this evening, Kelly and her family and I hop in the Ranger, an ATV they’ve just bought for hunting trips, and tour their neighborhood. They make it a point to take me over into the next subdivision, which is at a lower elevation along the San Jacinto River. It’s amazing to me how much of a difference it is between their subdivision, which was spotless, and the next one over, which was devastated. The mud line along shrubs and trees show just how high — and how scary — the river got.

Tree branches trapped in the Wallisville Road bridge over Greens Bayou on Sept. 8, nearly two weeks after Hurricane Harvey first hit Houston, show how high the waters climbed on the city’s east side. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

Sept. 8

New day, another opportunity for stories and content. I say my goodbyes to my hosts, as I’ll be heading for the airport in the late afternoon, and head for Christian Tabernacle Church. I want to be there at 10 a.m., when service begins. I make it on time, and there was a line winding its way through the parking lot as soon as I got there.

Getting out of my car, the scene is full of sound. Somber music is playing, and a young man is preaching into a microphone, projecting Bible passages meant to encourage those in line to not give up in the face of adversity. They wait their turn to get supplies in the gymnasium.

Set up nearby in the parking lot is a Tyson’s Meals that Matter cook station, and I camp out there for a while. I see all manner of people. There's a week-old baby with her mom in the Tyson food line. Welcome to this world, kid.

I'm shown a nearby area where flooding was so bad that a high school went under water, if you don't count the few inches that didn't, I’m told.

Hurricane Harvey impacted many employees at Tyson Foods’ processing facility on Houston’s east side. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

Time to move again. I decide to head to the nearby Tyson processing facility. The HR manager there, Rosa Cruz, hasn't responded to my requests for interviews, so I'll try in person. I know that she's been busy helping the many employees impacted by the hurricane cope with their current hardships. It's a large plant, particularly compared to the mostly mom-and-pop size shops I see here. I walk through the parking lot snapping photos and shooting video, hoping to enter as an employee would. There's a secure turnstile door, and an employee taking a break on the other side says I'll have to go through the main security entry. I do. The guard tells me Rosa isn't there and I can't go to the office without an appointment.

So I decide to go and find the ruined high school. It's on the way to the airport. I take a wrong turn at one point, and Google Maps is warning me that I’ll need to park the car and get to my destination by foot. I realize I’m not where I want to be and turn around, recalibrating to the high school. Houston is flat, only about 80 feet above sea level, and it's hard to imagine in dry times where and why some areas were flooded so much worse than others. It becomes clearer when I see the giant ventilation tubes sucking air out of the windows of the high school and a crew of dozens of Mississippians working to remove and dump its ruins.

Impacted residents pick up food from a cook site set up by Tyson Foods’ Meals That Matter program at Christian Tabernacle Church on Houston’s east side. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

Cleanup crew members on break in any shady spot they can find see me with a video camera, and compete with each other for what they thought would be air time — “you can interview me!” “No, interview me!” They, too, have become accustomed to a media presence here. I see stacks of gym floor, which I’m told was found floating on about four feet of water. I later see on news reports shots of the gym and it looks like a skateboard park, the water having warped the floor so badly that it created all sorts of undulations.

A drive around the neighborhoods surrounding the high school show more heaping helpings of gutted-out trash on the curbs. I capture more video, more photos, and proceed to the highway for a return to the airport.

Afterword

The Texas state flag looms large over the Montgomery County Fairgrounds in Conroe, Texas, where Tyson Foods established a distribution center for its Meals That Matter disaster relief program. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

After returning my rental, on which I put 500 miles, and getting through security and all, I make my way to my gate. As luck would have it, there’s a bar directly across from it. And, yes, I need a beer. I need more than one. I’m exhausted, and have so much in my head. I’m kind of staring blankly, through everyone around me. I can’t pretend to have seen the worst of this storm, and don’t at all want to dramatize, but I can feel this magnitude hitting me — now that I’ve stopped all this running around, all this in and out of the car, all these interviews, all this video-taking, photo-taking, video- transferring and photo-transferring, all the successes, the hospitable people willing to help and all the dead ends, the inhospitable people inclined to hang up the phone or show me the door.

Next to me at the bar is a dude also mostly keeping to himself. I find out that he works for Medline, a maker and distributor of healthcare products. He was here helping in recovery efforts, and says that some of his coworkers left early to get home to Florida to board up their homes in preparation for Hurricane Irma. News reports on TVs overhead make their predictions.

On the plane, I get to thinking about the disturbing psychology of all this.

We compare. We one-up, like competitors. Harvey was huge. Irma’s going to be bigger. When we’re watching these events unfold from afar, do we almost feel a disappointment when these storms maybe don’t live up to the hype? (Harvey more than did.) Do you want to see these stunning, heart-sinking images of damage? Do I feel, as a reporter who just spent four days in Houston, almost undermined by the next storm? Really, Irma?

Photo credit: Bert Ganzon

With this feeling of guilt — the feeling that on one level what I’ve been doing here is almost selfish, like calling it a success or feeling accomplished when I’ve swooped in and captured someone’s heartbreak — I start to piece together the fragments of my mind to form a purpose in this trip. I start to think about the purpose of this story. What is the story?

And when I start to think about all the people I’ve met, and what they’re going through, I realize that this isn’t a story about the bad stuff that happened to the meat processing community here. It’s about people. It’s about people helping people. It’s about humanity. Humanity. Period.